Publication Details

“For Esme – With Love and Squalor” was published in The New Yorker on April 8, 1950. It was later collected in Nine Stories (1953)

Character List

Staff Sergeant X (also The Narrator)

Narrator of the story, who has suffered shell shock and is telling us the story of a special child he met right before his unit participated in the D Day landings, as well as the dark period he suffered after battle. The story is split parts, and in one part the narration is first person, in the other it is third person. The third person narration is the point in the story where the narrator is referred to as “Staff Sergeant X.”

Esme

The young girl who has a conversation with Sergeant X the day before he goes into battle, and subsequently sends him a letter that reaches him once the battle is over. In the beginning of the story, we are told that Esme is getting married, and that she invited Sergeant X to the ceremony, even though she only met him once.

Charles

Esme’s little brother, a source of comic relief in the story and the focus on many critical studies along with the two main characters.

Corporal Z (Clay)

Sergeant X’s roommate after the battle. Some critics say he is the foil to Sergeant X’s character, and others say he represents the “squalor” from the title. He is crass and crude, and very much a caricature of a young, toughened Army grunt.

Miss Megley

Esme and Charles’ governess. She has a small role in the story, mainly as a not-very-good governess who allows the children to sit with and talk to Sergeant X.

Staff Sergeant X’s Wife

Barely mentioned.

Mother Goucher

Sergeant X’s mother-in-law. Mentioned at the beginning of the story.

Background

Salinger: A Biography by Paul Alexander tells us:

“As soon as The New Yorker published ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor,’ Salinger began to hear from readers. On April 20, he wrote to Lobrano from Westport to tell him that he had already gotten more letters about ‘For Esme’ than he head for any story he had published.”

Hamish Hamilton (a British publisher) wanted to publish a collection of Salinger’s stories. Salinger was reluctant. He ended up publishing Nine Stories (not with Hamilton), but “two months after Little, Brown published Nine Stories, Hamish Hamilton released the book in England. There was, however, one major difference between the American and British versions. Hamilton felt strongly that the generic name Nine Stories would have been the worst possible title to put on the book and he somehow convinced Saligner to let him use as the title for the collection “For Esme – With Love and Squalor,” the story that was perhaps Salinger’s most famous in England if not the United States as well. To the public, Hamilton also finessed the fact that the book was a collection of stories by emphasizing in the advertising copy the idea that For Esme was the next book from the author of The Catcher in the Rye. Hamilton wanted to downplay the truth, since story collections never sell as well as novels.”

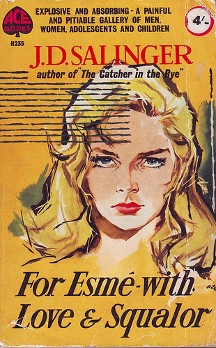

Hamilton put the book out in 1953. It did not do well financially, but was well-received critically. Later the same year, Hamilton sold the book to Ace Books – a mass market publisher. They did not usually deal with “real literature.” Hamilton thought it was a good financial decision. Ace published the book with an inappropriate picture of an older, sexy blond girl on the cover. Hamilton didn’t consult Salinger before the sale, and Salinger was truly angry. Salinger never spoke to him again.

Plot Synopsis

The story opens with a first person narrator informing the reader that he received an invitation for an English wedding that will take place April 18th. He expresses a desire to go to the wedding, but tells the reader that his mother-in-law (Mother Grencher) is coming to visit, so he can’t. He says that he has “jotted down a few revealing notes on the bride as I knew her almost six years ago.”

The narrator then tells us that in April of 1944 he was stationed in Devon, England. We learn that he is American, that he was an enlisted man, and that he was part of a “rather specialized pre-Invasion training course.” His unit trained for three weeks, and then they were scheduled to be a part the “D Day Landings.” On this last night before the deployment, the narrator had already packed his bags, so he gets on his outdoor things and walks into town.

Once in town, he stops at a church where schoolchildren are having choir practice. He notices one child in particular, who has a clearer and nicer voice than the other children. She is around thirteen years old, and is a very pretty child. After the song ends, the narrator goes to a tearoom. Soon after, the pretty young girl from choir practice comes into the tearoom with a governess and a little boy.

The girl eventually approaches the narrator, and he asks her to join him. The conversation that takes place is witty and delightful, and the narrator is obviously very impressed by his companion’s intelligence. The girl, named Esme, tells the narrator about her aspirations, her past, her family, and we learn that her father has died in the war.

Esme’s brother Charles comes over and tells the narrator a joke, “What did one wall say to the other wall? Meet you at the corner!” Charles is very amused by his joke and laughs uproariously.

The narrator notices the large wristwatch that Esme is wearing. It belonged to her father. She, having learned that the narrator was a “professional short-story writer” before the war, tells the narrator that she wishes he would write a story for her – and that she prefers “stories about squalor.”

Charles tells his joke again, and the narrator finishes the punch line. Charles gets angry and stomps away, and soon it is time for the children to leave the tea house. Before she goes, Esme asks the narrator if he wants for her to write to him, because she writes “extremely articulate letters.” The narrator gives her his rank and name so she can write to him. She tells him she’ll write to him first so that he doesn’t feel “compromised” in any way. Charles and Esme come back into the tea room because Charles wants to kiss the narrator goodbye. The narrator asks Charles “What did one wall say to the other wall?” and Charles happily replies, “Meet you at the corner!”

The narration shifts and we have the first person narrator telling us that “this is the squalid, or moving, part of the story, and the scene changes.” The narration shifts to a third person narrator and the setting of the story shifts to Gaufurt, Bavaria “several weeks after V-E Day.”

Staff Sergeant X, possibly recovering from a nervous breakdown and suffering shell shock. He is not able to sleep, he is chain-smoking, his gums are bleeding, and he is generally in ill health. His friend Clay, whom he refers to as “Corporal Z” talks to him about his girlfriend Loretta, and tries to get X to come to some parties in town. X declines, and stays in his room alone. He finds a pile of mail that he had not yet opened, and opens a letter that is from Esme.

In the letter Esme apologizes for her delay in writing, and asks him to “reply as soon as possible.” She sends her father’s wristwatch in the package, and at the end of the letter Charles has added “HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO HELLO LOVE AND KISSES CHARLES.”

X finally starts to feel sleepy, and the reader is left with the feeling that he might come out of this after all.

Reviews

Review of Nine Stories in The New York Times – “Threads of Innocence” April 5, 1953 by Eudora Welty

She calls the story itself “remarkable” and in a subsequent paragraph says the following about the stories in general, though the quote applies directly to “For Esme.”

“The stories concern children a good deal of the time, but they are God’s children. Mr. Salinger’s work deals with innocence, and starts with innocence: from there it can penetrate a full range of relationships, follow the spirit’s private adventure, inquire into grave problems gravely-into live and death and human vulnerability and into the occasional mystical experience where age does not, after a point, any longer apply. Mr. Salinger’s world urban, suburban, family, mostly of the Eastern seaboard is never a clue to the way he will treat it: he seems to write without the preconception of shackling things.”

She goes on to say

“What this reader loves about Mr. Salinger’s stories is that they honor what is unique and precious in each person on earth. Their author has the courage-it is more like the earned right and privilege-to experiment at the risk of not being understood. Best of all, he has a loving heart.”

Review of Nine Stories in The New York Times – “Books of the Times” April 9, 1953 by Charles Poore

“‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor’ is still the best short story that has come out of World War II. Now all we ask is that Mr. Salinger put away his Halloween tricks and write as good a novel of World War II. He can do it. Make no mistake about that.”

The New York Times – “Aw, The World’s A Crumby Place” July 15, 1951 by James Stern

“This girl Helga, she kills me. She reads just about everything I bring into the house, and a lot of crumby stuff besides. She’s crazy about kids. I mean stories about kids. But Hel, she says there’s hardly a writer alive can write about children. Only these English guys Richard Hughes and Walter de la Mare, she says. The rest is all corny. It depresses her. That’s another thing. She can sniff a corny guy or a phony book quick as a dog smells a rat. This phoniness, it give old Hel a pain if you want to know the truth. That’s why she came holelring to me one day, her hair falling over her face and all, and said I had to read some damn story in The New Yorker. Who’s the author? I said. Salinger, She told me. J.D. Salinger. Who’s he, I asked. How should I know, she said, just you read it.

‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor’ was this story’s crumby title. But boy, was that a story. About a G.I. or something and a couple of English kids in the last war. Hel, I said when I was through, just you wait till this guy writes a novel. Novel, my elbow, she said. This Salinger, he won’t write no crumby novel. He’s a short story guy. Girls, they kill me. They really do.”

**The review goes on to, in its mocking way, make a little fun of The Catcher in The Rye, but you can see that section of this piece on Catcher’s Reader’s Guide.** editor note

Criticism and Scholarly Articles

Gwynn & Blotner: “The High Point of Salinger’s Art: ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor‘”

“at the outset, it might be well to consider Salinger’s major fictional victory-the victories being the only reason for considering any of the failures that punctuate his unique career. The high point of his art, the moment at which particular narrative and general truth are identified most successfully with one another, comes in his most famous story, ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor.'”

Ihab Hassan – “The Rare Quixotic Gesuture“

“The second phase of Salinger’s career includes at least three stories which are among the very best he has written: ‘Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut,’ ‘Down at the Dinghy,’ and ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor.’ This phase also marks the level of his most sustained achievement. The cellophane transparency and geometric outlines of the earlier pieces give way to a constant energy of perception and irritation of the moral sense. Here, in a world which has forfeited its access to the simple truth, we are put on to the primary mendacity. Here, where the sources of love are frozen and responsiveness can only survive in clownish attire, we are jolted by the Zen epigraph: ‘We know the sound of two hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping?”

*editor note: what will follow are selected pieces of critical essays related to the main themes in the story*

Targeted Literary Criticism – The Redemptive Power of Love in “For Esme – With Love and Squalor”

Alfred Kazin – “Everybody’s Favorite“

“for myself, I must confess that the spiritual transformation that so many people associate with the very sight of the word ‘love’ on the printed page does not move me as it should. In what has been considered Salinger’s best story, ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor,’ Sergeant X in the American Army of Occupation in Germany is saved from a hopeless breakdown by the beautiful magnanimity and remembrance of an aristocratic young English girl. We are prepared for this climax or visitation by an earlier scene in which the sergeant comes upon a book by Goebbels in which a Nazi woman had written, ‘Dear God, life is hell.’ Under this, persuaded at last of his common suffering, even with a Nazi, he writes down, from The Brothers Karamazov, ‘Fathers and teachers, I ponder, “What is hell?” I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.

But for the love that Father Zossima in Dostoevsky’s novel speaks for is surely love for the world, for God’s creation itself, for all that precedes us and supports us, that will outlast us and that alone helps us to explain ourselves to ourselves.”

editor note: Is “love” what saves Sergeant X? If so, what type of love saves him?

Maxwell Geismar – “The Wise Child and The New Yorker School of Fiction“

Geismar says that the story “concerns a beautiful, dignified, precocious upper-class English maiden of thirteen who saves an American soldier from a nervous breakdown. There is no doubt of Esme’s grace and charm (or of her social standing), but only whether, in this case, an adolescent’s romantic affection can replace the need for mental therapy.”

editor note: it is certainly doubtful as to whether Esme’s affection for Sergeant X is romantic.

Dan Wakefield – “The Search for Love“

“Having seen suffering – human suffering – as the inability to love, Sergeant X is shortly afterward, unexpectedly, saved by love.”

**also refers to Salinger’s “unspoiled love of children.”

Arthur Heiserman and James Miller – “Some Crazy Cliff“

“The hero of ‘For Esme’ is an American soldier who, driven to near psychosis by five campaigns of World War II and a moronic jeep mate, is saved in a act of childish love by two remarkable English children. Just as surely as war and neurosis are both manifestations of the lack of love, the soldier discovers peace and happiness are manifestations of love’s presence. The Love must be spelled with a capital; for it is not the alienated, romantic love of the courtly romance.”

Targeted Literary Criticism – A Context for Squalor in “For Esme – With Love and Squalor”

Warren French – “A Nine Story Cycle“

“In the second scene, the narrator, now for unfathomable reasons masquerading as Sergeant X, has indeed become acquainted with the squalor that he proceeds to chronicle. Possible to illustrate Esme’s charge that Americans act like animals, which the narrator had chided as snobbish, Salinger exhibits the most grotesque array of insensitive egotists possibly ever summoned up in so few words.”

Goes on to say that Clay (Corporal Z) is the most squalid aspect of the story.

editor note: What do you think of French’s statement that the narrator’s shift is “unfathomable?” What is the reason for the narrative shift? Is it, in fact, brought on by the squalor all around him?”

Gwynn and Blotner – “One Hand Clapping“

“To make any kind of contact with Joseph Goebbels is to be overwhelmed by the very type of psychotic hatred for everything weaker or more human than itself. His diaries show him to be ‘the unflagging motive force behind the vicious Antisemitism of the Nazi regime’ as Hugh Gibson says, whose ‘aim was the extermination of all Jews’; an ex-catholic, he planned to ‘deal with the churches after the war and reduce them to impotence.’ It was this man, the holder of a bona fide doctorate, who in 1933 personally selected and burned thousands of printed pages in which man had communicated with man. Less known that the genocide and the book-burning is Goebbels’ hatred for humanity itself. In 1925 he wrote in his diary: ‘I have learned to despise the human being from the bottom of my soul. He makes me sick to my stomach.’ A year later he concluded that ‘The human being is a canaille.’

But as Louis Ochner says, ‘Nobody who has not lived under Nazism can grasp how absolute was Goebbels’ control of the German mind.'”

Gwynn and Blotner go on to say that this Nazi mindset is a “nonlove” and it provides “a profound objective correlative for the love and ‘squalor’ experience by Sergeant X.” They describe four ‘squalid’ forces in the story:

1. The present narrator’s relationship with his wife and mother.

2. Sergeant X’s state of mind PRIOR to meeting Esme – the “dullness of pre-Invasion training.”

3. The war itself.

4. Clay and his girl Loretta, post war trauma, and X’s brother’s request for souvenirs.

They go on to describe the four forces of love that fight the forces of squalor:

1. The unexpected invitation to Esme’s wedding.

2. Meeting Esme

3. X’s written response to the female Nazi – thus serving to “equate himself wither simply as human beings against the total war they have suffered in…”

4. X receiving the letter and wrist watch from Esme.

Ihab Hassan – “A Rare Quixotic Gesture“

Hassan says, “Squalor, real and tangible like the dust of death, has settle all about him – until he finds a battered package from Esme, in which she has quixotically enclosed her dead father’s watch.”

John Wenke – “Sergeant X, Esme, and the Meaning of Words“

“Nonetheless, the very fact that the story is even told in the first place suggests that there is a way to be immersed in squalor, recognize it as such, and eventually overcome it. ‘For Esme’ depicts extreme human misery, the suffering of being unable to love…”

Targeted Literary Criticism – War is Hell in “For Esme – With Love and Squalor”

editor note – for more information on World War II as a contextual subject regarding Salinger’s work as a whole, visit the World War II Context section under Context. (link forthcoming)

Henry Grunwald – “The Invisible Man: A Biographical Collage” – “Sonny: An Introduction”

“By 1944 the author was stationed in Tiverton, Devonshire, training with a small counter-intelligence detachment of the 4th Infantry Division – almost exactly the situation of Sergeant X, the tormented hero of the warmest and best of the Nine Stories, ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor’ (the author, like Sergeant X, passed the time by listening to choir practice at a Methodist church in Teverton.”

“On June 6, five hours after the first assault forces hit Utah Beach, Salinger landed with the 4th in Normandy, stayed with the division through the Battle of the Bulge. He was an aloof, solitary soldier whose job was to discover Gestapo agents by interviewing French civilians and captured Germans.”

George Steiner – “The Salinger Industry“

“‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor’ is a wonderfully moving story, perhaps the best study to come out of hte war of the way in which the greater facts of hatred play havoc in the private soul.”

Eberhad Alsen – “New Light on the Nervous Breakdowns of Salinger’s Sergeant X and Seymour Glass“

“We know about Salinger’s breakdown from a letter that he wrote to Ernest Hemingway from Germany in 1945 (the two had met twice during the war). In this undated letter, Salinger writes that he has checked himself into a ‘General Hospital in Nurenburg’ because he has been in ‘an almost constant state of despondency.'”

Alsen goes on to talk about Salinger’s exposure to a concentration camp and the horrors he witnessed there:

“The sights at the Hurlach camp were no less gruesome than the smell. In addition to 268 burned corpses, the GIs found close to a hundred bodies scattered over the camp, along a path to the railroad tracks, and in a nearby forest…Some of the photos show blackened bodies still smoldering in the ruins of the burned-down barracks…Salinger encountered the smell of burning flesh, which he said he would never be able to get out of his nostrils.”

He calls “For Esme” Salinger’s “most autobiographical story.”

William Purcell – “World War II and the Early Fiction of J. D. Salinger“

“In reviewing the stories that were eventually preserved in Salinger’s four books, it becomes quickly apparent that none, with the notable exception of ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor,’ openly draws upon the war for its primary themes. Of those remaining few in which the war does appear at all, it is mostly as a dark event lurking somewhere in the backgrounds of the main characters.”

Targeted Literary Criticism – “For Esme – With Love and Squalor” – The Anti-Esme Camp

John Antico – “The Parody of J.D. Salinger: Esme and the Fat Lady Exposed“

“The usual interpretation of ‘For Esme’ has it that the love of a thirteen-year-old English girl reaches through the squalor of war to cure the war-weary Sergeant who is on the point of a nervous breakdown. Critics are often quite effusive over the power of love in the story…Such an interpretation, however, makes the story the ‘popular little tear-jerker’ that Leslie Fielder calls it, but my contention is that this is not what Salinger intended. A careful examination of this story will demonstrate that ‘For Esme’ is a parody of the typical sentimental war story in which the Love for the Girl Back Home boost the Morale of the Intrepid War Hero and Saves him from Battle Fatigue. Instead of Esme’s love, it is Sergeant X’s sense of humor that ‘saves him;’ instead of an innocent, graceful, and magnanimous Esme, we actually have a precocious snob and a cold, affected and aristocratic brat – in a word, a phony. Instead of celebrating the power of love, Salinger is satirizing what so often passes as love in bad fiction.”

John Romano – “Salinger Was Playing Our Song” from The New York Times June 3, 1979

Romano talks about the need to dive into Salinger’s less-known works (less known than The Catcher in the Rye) and gives a brief outline of ‘For Esme’ and quotes the exchange between the American soldier and Esme where she talks about her father. He goes on to say:

“I’ve quoted this story in such bulk mainly because it’s the sort of diminutive masterpiece we should be reminded of occasionally; also because it’s strong and dissonant and, finally, adult. We can say about ‘Esme’ what we can’t, or at least haven’t, about The Catcher in the Rye; that in it adolescent vision and adult experience hold each other in a useful tension, a mutual illumination. Holden was an inveterate, perhaps manic spotter of ‘phonies’ – nightclubbing phonies, academic phonies, society phonies, sexual phonies. But Esme, all touchingly, is a phony herself, phony as only a 13-year-old girl overly proud of her vocabulary can be.”

John Hermann – J.D. Salinger: Hello Hello Hello

“…I should like to suggest, contrary to some recent interpretations, that it is Charles, rather than Esme, who is the key to the story. It is his riddle of what one way say (sic) to another: ‘Meetcha at the corner,’ which is the nexus between Sergeant X and the world, and it is Charles’ final, spontaneous, and insistent ‘Hello Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello….’ affixed to the end of Eme’s letter, that brings Sergeant X’s ‘F-A-C-U-L-T-I-E-S back together.”

Hermann goes on to compare and contrast Esme and Charles, saying that Esme is one of the “Silly Billy parrots” the choir director talks about and that Charles freer and therefore a truer example of innocence. He says that Esme is too caught up in facts and statistics. He concludes:

“Much as we like Esme’s intellegence, poise, and breath-taking levelheadedness, it is her brother Charles, with the orange eyes and the arching back and the smacking kiss, who knows without counting the house, without 3:45 and 4:15 PMs, the riddles of the heart.”

Targeted Literary Criticism – “For Esme – With Love and Squalor” – Arguments for Esme

Most criticism sees Esme as the catalyst that brings Sergeant X out of his state. One has to wonder if Hermann really pulled together enough support for his argument. Obviously others asked the same question.

Robert M. Brown – “Rebuttal: In Defense of Esme”

“But Esme’s love of truth is simply part of her admirable integrity. She is still a child enough not to have lost wonder and curiosity; her intelligence has not been corrupted by wishful thinking (her cool appraisal of her mother, her refusal, which Mr. Hermann thinks abnormal, to pretend that her hair is curly when it’s only wavy). True enough, her literalness is a trifle comic, but it is not morally disabling, as it might be in an adult.”

He goes on to defend Esme against every slight Hermann puts her way, and concludes with:

“When Esme asks X if he, like her aunt, finds her terribly cold, the reply of this ordinarily reserved man is ‘absolutely not – very much to the contrary, in fact.’ I will back him against the aunt, the choir coach and Mr. Hermann.”

Mike Tierce – “Salinger’s ‘For Esme – With Love and Squalor'”

“Actually, it is the combination of the two – Esme and Charles – the saves Sergeant X. Because Esme represents the world fo science, rationality, and materialism and Charles represents the world of emotional spontaneity, they personify the poles of life with which X must come to grips…

The narrator’s assertion that Charles’ riddle is the ‘key question’ is absolutely correct. The riddle ‘what did one wall say to the other way’ followed by the punch line ‘meet you at the corner’ illustrates the exact nature of X’s reconciliation of opposites.”

For a complete bibliography of all scholarly works that mention “For Esme – With Love and Squalor” and for more information, check back soon!

You have incredible knowlwdge listed here.