Publication Details:

J.D. Salinger, “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut” The New Yorker. March 20, 1948. p 30-36. Print.

Salinger, J.D. “”Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut”” Nine Stories. Boston: Little, Brown, 1953. Print.

Character List:

Eloise Wengler – the woman of the house where the story is set, mother of Ramona and wife of Lew, former girlfriend of Walt Glass.

Mary Jane – Eloise’s former college roommate, come to have a visit with Eloise.

Ramona Wengler – Eloise and Lew’s daughter, has an imaginary friend named Jimmy Jimereeno who dies during the course of the story.

Lew Wengler – Eloise’s husband – is mentioned but does not appear in the story.

Walt Glass – only referred to a “Walt,” Eloise’s old boyfriend who called drafted during their relationship and died in WWII. Is a member of the Glass family.

Grace – The Wengler’s housekeeper.

Summary:

The story opens with Mary Jane arriving at Eloise’s house for a quick visit. The women had been roommates in college, though neither of them graduated. Eloise had been caught with a solider in her dorm (maybe that soldier was Walt?) and Mary Jane left college to get married to another soldier who spent two of the three months they were married in jail.

Eloise and Mary Jane start drinking and talking about their college days, and about mutual friends. Mary Jane keeps insisting that she needs to leave, but Eloise keeps the drinks coming and they both sit and drink and smoke for a while. Eloise’s daughter, Ramona, comes in and Mary Jane speaks to her. Ramona has an imaginary friend named Jimmy Jimereeno. Ramona later informs Mary Jane and Eloise that Jimmy is dead, having been hit by a car.

Eloise talks about Walt, her ex-boyfriend, and gets very sentimental. She tells Mary Jane that one time she injured her ankle, and Walk said, “Poor Uncle Wiggily,” talking about her ankle. The conversation moves to Lew, Eloise’s husband, and Mary Jane asks why Eloise never told Lew about Walt, and Eloise waxes philosophical about men and marriage, stating that men never want to know about the men you dated before them. Mary Jane and Eloise discuss how Walt died in the war, and Eloise continues to get even more emotional.

Lew calls and we hear Eloise’s side of the conversation. The weather is bad and Lew is not sure when he’ll be home. Later, Grace asks Eloise if her husband can stay the night, because the weather is so bad. Eloise tells her that he cannot stay, and Grace acquiesces.

Mary Jane passes out on the couch, and Eloise goes upstairs to check on Ramona, who she had sent upstairs after determining she was feverish after Ramona informed the women about Jimmy’s unfortunate accident. Ramona is only sleeping on one side of her bed, and Eloise asks her why, since Jimmy is dead. Ramona tells her that she is making room for her new friend, Mickey Mickeranno. Eloise is cross with Ramona, telling her to get in the center of the bed immediately. Ramona is afraid and shuts her eyes.

Eloise is maudlin, picks up Ramona’s glasses which are sitting on the side table, lenses up and stems down. She holds them to her teary cheek, and repeats “Poor Uncle Wiggily” over and over again. She puts the glasses back down on the nightstand, lenses down, still wet with her tears. She leans over her daughter, who has been crying, and kisses her and staggers out of the room.

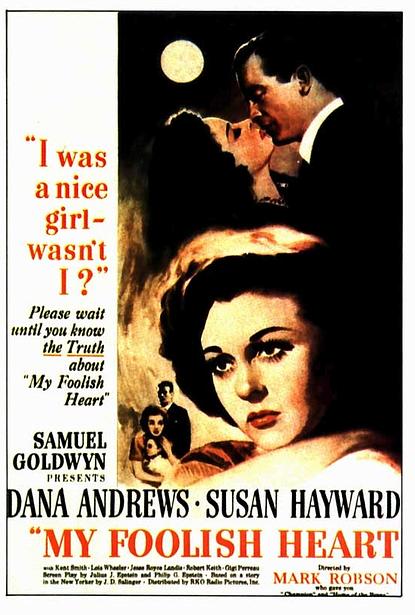

Eloise goes downstairs, wakes up Mary Jane, and reminds her of a time that someone at school made a mean comment about a dress Eloise wore. She says that she cried all night about it. She asks Mary Jane, “I was a nice girl…wasn’t I?”