Publication Details:

The New Yorker January 31, 1948. Pages 21-25. Later published as part of the collection Nine Stories.

Character List:

Seymour Glass

A young, newlywed soldier who has just returned from the war. He’s on vacation with his wife in Florida.

Muriel Glass

Seymour’s wife.

Muriel’s Mother

Muriel’s mother, who expresses great concern about Seymour’s state of mind.

Sybil Carpenter

A four-year-old little girl who interacts with Seymour on the beach. She and her mother are staying in the same hotel as Seymour and Muriel.

Mrs. Carpenter

Sybil’s mother.

Sharon Lipschutz

Another little girl who is staying in the same hotel.

Plot Synopsis:

The story opens on Muriel alone in she and Seymour’s hotel room. Her call finally gets connected, and she proceeds to have a long conversation with her mother, who expresses a great deal of concern about Muriel because she seems to think that Seymour is crazy.

The scene changes. Sybil is on the beach, having suntan lotion applied by her mother. Her mother leaves to go back up to the hotel to have a drink

Sybil walks down the beach and approaches a man (Seymour) who is lying in his robe on the beach. He and Sybil have a characteristically Salingeresque conversation wherein Seymour tells Sybil to keep an eye out for bananafish. He exaplains that bananafish “lead a very tragic life” in that they swim into a hole underwater and gorge themselves on bananas so much that they can’t get out and die.

After he and Sybil’s time in the water Seymour goes back into the hotel. He has a strange outburst at fellow hotel guests in the elevator, goes back into his hotel room, looks at his wife, retrieves his gun from his luggage, sits on the bed, and shoots himself in the head.

Reviews:

For reviews of Nine Stories in general, please see the Nine Stories Primary Text Page.

Criticism:

for an overview of each critical article, click on the link to each, or visit our Bibliographical Journal Article section.

Fassano, Anthony: “Salinger’s A Perfect Day for Bananafish” Explicator (66:3) 2008, 149-50

Greiner, Donald J: “Updike and Salinger: a literary incident.” Critique: studies in contemporary fiction (47:2) 2006, 415-30.

Lacy, Robert: “Sing a song of Sonny” Sewanee Review (113:2) 2005, 309-316

Smith, Dominic: “Salinger’s Nine Stories: fifty years later” Antioch Review (61:4) 2003, 639-49

Alsen, Eberhard: “New light on the nervous breakdowns of Salinger’s Sergeant X and Seymour Glass” CLA Journal (45:3) 2002, 379-87

Malcolm, Janet: “Justice to J.D. Salinger” New York Review of Books (48:10) 2001, 16-21

Lane, Gary: “Seymour’s Suicide Again: A New Reading of J.D. Salinger’s ‘A Perfect Day for Bananafish'” Studies in Short Fiction 10.1 (winter 1973) p 27-34 reprinted in Short Stories for Students Ed David A Galens Vol. 17. Detroit Gale, 2003 from Literature Resource Center

Moran, Daniel: “Critical Essay on ‘A Perfect Day for Bananafish'” Short Stories for Students. Ed. David A. Galens Vol. 17 Detroit Gale, 2003 from Literature Resource Center

Allsop, Kenneth: The Dissentient Mood “The Angry Decade: A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen-Fifties

Cotter, James Finn: “A Source for Seymour’s Suicide: Rilke’s Voices and Salinger’s Nine Stories” papers on Language and Literature 25.1 (Winter 1989) p83-98 reprinted in Short Stories for Students

In JSTOR

Levine, P: “JD Salinger: The Development of the Misfit Hero” Twentieth Century Literature 1958

Wiegand, W: “JD Salinger: seventy-eight bananas” Chicago Review, 1958

Baskett, SS: “The Splendid/Squalid World of JD Salinger” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, 1963

Smith, D: “Salinger’s Nine Stories: Fifty Years Later” The Antioch Review, 2003

Glazier, L: “The Glass Family Saga: Argument and Epiphany” College English, 1965

Boe, AF: For Seymour: With Love and Judgement” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, 1963

Bryan, JE: “Salinger’s Seymour’s Suicide” College English, 1962

Mazzaro, JL: “People in Glass Houses” The North American Review, 1964

Other sources

O’Hearn, S: “The development of Seymour Glass as a figure of hope in the fiction of JD Salinger” Open Dissertations and Theses, 1982

Themes and Discussion Points:

As you will learn if you browse the critical articles listed above, there are a myriad of things that Salinger scholars like to discuss when talking about “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.” Here is a list of critical questions that the articles above will help you answer.

1. Why do you think Seymour kills himself at the end of the story?

2. Why did the author choose that fate for Seymour?

3. How do you explain Salinger’s need to revisit the topic of Seymour so often in his later work? Do you think he regretted killing Seymour off in “A Perfect Day for Bananafish?”

4. What do you think of the way that shell shock/war trauma is characterized in the story? Do you think that Muriel is sympathetic to Seymour’s mental condition?

5. What is the significance of Sybil? Why do you think Seymour relates to Sybil better than to others?

6. What is the significance of feet in this story? Why does Seymour kiss the bottom of Sybil’s foot, and why does Seymour accuse the lady in the elevator of looking at his feet?

7. Why does Seymour want Sybil to look for Bananafish in the first place, and what is a Bananafish?

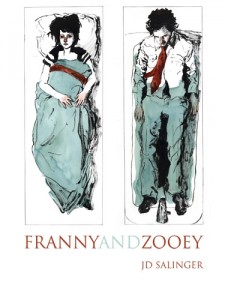

photo credit of Noah Sneider’s incredible work – http://www.noahsneider.com