Letters to J.D. Salinger edited by Chris Kubica and Will Hochman

MLA Citation:

Book Jacket Copy:

“He published his only novel more than fifty years ago. He has hardly been seen or heard from since 1965. Most writers fitting such a description are long forgotten, but if the novel is The Catcher in the Rye and the writer is J.D. Salinger…well, he’s the stuff of legends, the most famously reclusive writer of the twentieth century. If you could write to him, what would you say?

Salinger continues to maintain his silence, but Holden Caulfield, Fanny and Zooey, and Seymour Glass–the unforgettable characters of his novel and short stories–continue to speak to generations of readers and writers. Letters to J.D. Salinger includes more than eighty personal letters addressed to Salinger from well-known writers, editors, critics, journalists, and other luminaries, as well as from students, teachers, and readers around the world, some of whom have just discovered Salinger for the first time. Their voices testify to the lasting impression Salinger’s ideas and emotions have made on so many diverse lives.”

Reader’s Guide – “Uncle Wiggily In Connecticut”

Publication Details:

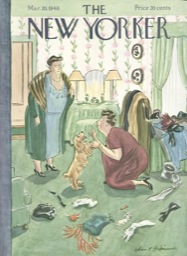

J.D. Salinger, “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut” The New Yorker. March 20, 1948. p 30-36. Print.

Salinger, J.D. “”Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut”” Nine Stories. Boston: Little, Brown, 1953. Print.

Character List:

Eloise Wengler – the woman of the house where the story is set, mother of Ramona and wife of Lew, former girlfriend of Walt Glass.

Mary Jane – Eloise’s former college roommate, come to have a visit with Eloise.

Ramona Wengler – Eloise and Lew’s daughter, has an imaginary friend named Jimmy Jimereeno who dies during the course of the story.

Lew Wengler – Eloise’s husband – is mentioned but does not appear in the story.

Walt Glass – only referred to a “Walt,” Eloise’s old boyfriend who called drafted during their relationship and died in WWII. Is a member of the Glass family.

Grace – The Wengler’s housekeeper.

Summary:

The story opens with Mary Jane arriving at Eloise’s house for a quick visit. The women had been roommates in college, though neither of them graduated. Eloise had been caught with a solider in her dorm (maybe that soldier was Walt?) and Mary Jane left college to get married to another soldier who spent two of the three months they were married in jail.

Eloise and Mary Jane start drinking and talking about their college days, and about mutual friends. Mary Jane keeps insisting that she needs to leave, but Eloise keeps the drinks coming and they both sit and drink and smoke for a while. Eloise’s daughter, Ramona, comes in and Mary Jane speaks to her. Ramona has an imaginary friend named Jimmy Jimereeno. Ramona later informs Mary Jane and Eloise that Jimmy is dead, having been hit by a car.

Eloise talks about Walt, her ex-boyfriend, and gets very sentimental. She tells Mary Jane that one time she injured her ankle, and Walk said, “Poor Uncle Wiggily,” talking about her ankle. The conversation moves to Lew, Eloise’s husband, and Mary Jane asks why Eloise never told Lew about Walt, and Eloise waxes philosophical about men and marriage, stating that men never want to know about the men you dated before them. Mary Jane and Eloise discuss how Walt died in the war, and Eloise continues to get even more emotional.

Lew calls and we hear Eloise’s side of the conversation. The weather is bad and Lew is not sure when he’ll be home. Later, Grace asks Eloise if her husband can stay the night, because the weather is so bad. Eloise tells her that he cannot stay, and Grace acquiesces.

Mary Jane passes out on the couch, and Eloise goes upstairs to check on Ramona, who she had sent upstairs after determining she was feverish after Ramona informed the women about Jimmy’s unfortunate accident. Ramona is only sleeping on one side of her bed, and Eloise asks her why, since Jimmy is dead. Ramona tells her that she is making room for her new friend, Mickey Mickeranno. Eloise is cross with Ramona, telling her to get in the center of the bed immediately. Ramona is afraid and shuts her eyes.

Eloise is maudlin, picks up Ramona’s glasses which are sitting on the side table, lenses up and stems down. She holds them to her teary cheek, and repeats “Poor Uncle Wiggily” over and over again. She puts the glasses back down on the nightstand, lenses down, still wet with her tears. She leans over her daughter, who has been crying, and kisses her and staggers out of the room.

Eloise goes downstairs, wakes up Mary Jane, and reminds her of a time that someone at school made a mean comment about a dress Eloise wore. She says that she cried all night about it. She asks Mary Jane, “I was a nice girl…wasn’t I?”

Continue reading “Reader’s Guide – “Uncle Wiggily In Connecticut””

Justice to J. D. Salinger

MLA Citation:

First Paragraph:

“When J.D. Salinger’s “Hapworth 16, 1924”—a very long and very strange story in the form of a letter from camp written by Seymour Glass when he was seven—appeared in The New Yorker in June 1965, it was greeted with unhappy, even embarrassed silence. It seemed to confirm the growing critical consensus that Salinger was going to hell in a handbasket. By the late Fifties, when the stories “Franny” and “Zooey” and “Raise High the Roof-Beam, Carpenters” were coming out in the magazine, Salinger was no longer the universally beloved author of The Catcher in the Rye; he was now the seriously annoying creator of the Glass family.”

Continue reading “Justice to J. D. Salinger”

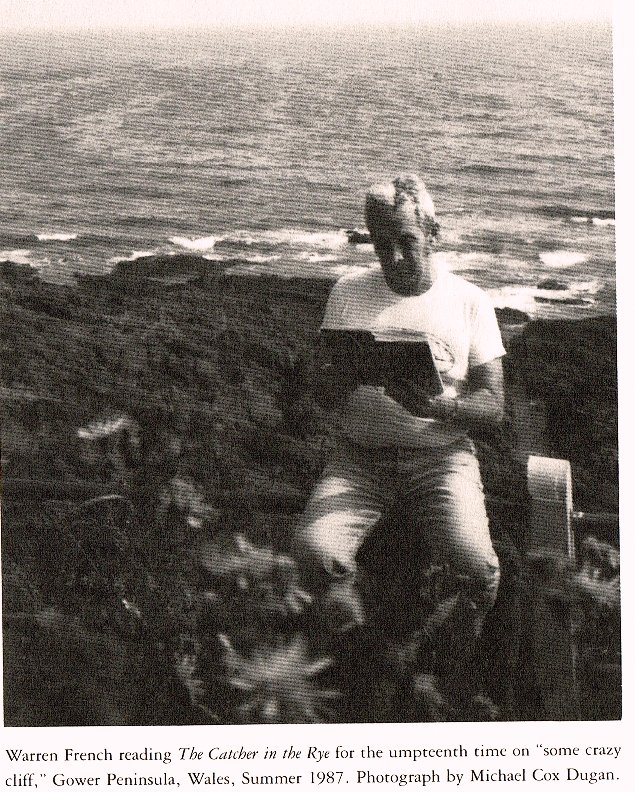

J.D. Salinger, Revisited by Warren French

MLA Citation:

French, Warren. J.D. Salinger, Revisted. Boston: Twayne, 1988. Print.

First Paragraph:

“The irony of the title of this book is that nobody visits J.D. Salinger at all without a rarely extended invitation, and certainly the least likely recipient of one would be a professional literary critic. Like many authors, Salinger feels that what he has to say can be found in his books and that readers need no outside guidance, although the tragic behavior of Mark David Chapman (John Lennon’s assassin) might suggest otherwise. (Chapman inaccurately cited Catcher in the Rye at his sentencing to justify his actions {see Chapter Three, n. 13}.) Anyway, I bring no news about Salinger himself, as I will be revisiting only the writings he has with increasing reluctance committed to print.”

from the Preface, page ix

Continue reading “J.D. Salinger, Revisited by Warren French”

Readers Guide – “A Perfect Day For Bananafish”

Publication Details:

The New Yorker January 31, 1948. Pages 21-25. Later published as part of the collection Nine Stories.

Character List:

Seymour Glass

A young, newlywed soldier who has just returned from the war. He’s on vacation with his wife in Florida.

Muriel Glass

Seymour’s wife.

Muriel’s Mother

Muriel’s mother, who expresses great concern about Seymour’s state of mind.

Sybil Carpenter

A four-year-old little girl who interacts with Seymour on the beach. She and her mother are staying in the same hotel as Seymour and Muriel.

Mrs. Carpenter

Sybil’s mother.

Sharon Lipschutz

Another little girl who is staying in the same hotel.

Plot Synopsis:

The story opens on Muriel alone in she and Seymour’s hotel room. Her call finally gets connected, and she proceeds to have a long conversation with her mother, who expresses a great deal of concern about Muriel because she seems to think that Seymour is crazy.

The scene changes. Sybil is on the beach, having suntan lotion applied by her mother. Her mother leaves to go back up to the hotel to have a drink

Sybil walks down the beach and approaches a man (Seymour) who is lying in his robe on the beach. He and Sybil have a characteristically Salingeresque conversation wherein Seymour tells Sybil to keep an eye out for bananafish. He exaplains that bananafish “lead a very tragic life” in that they swim into a hole underwater and gorge themselves on bananas so much that they can’t get out and die.

After he and Sybil’s time in the water Seymour goes back into the hotel. He has a strange outburst at fellow hotel guests in the elevator, goes back into his hotel room, looks at his wife, retrieves his gun from his luggage, sits on the bed, and shoots himself in the head.

Reviews:

For reviews of Nine Stories in general, please see the Nine Stories Primary Text Page.

Criticism:

for an overview of each critical article, click on the link to each, or visit our Bibliographical Journal Article section.

Fassano, Anthony: “Salinger’s A Perfect Day for Bananafish” Explicator (66:3) 2008, 149-50

Greiner, Donald J: “Updike and Salinger: a literary incident.” Critique: studies in contemporary fiction (47:2) 2006, 415-30.

Lacy, Robert: “Sing a song of Sonny” Sewanee Review (113:2) 2005, 309-316

Smith, Dominic: “Salinger’s Nine Stories: fifty years later” Antioch Review (61:4) 2003, 639-49

Alsen, Eberhard: “New light on the nervous breakdowns of Salinger’s Sergeant X and Seymour Glass” CLA Journal (45:3) 2002, 379-87

Malcolm, Janet: “Justice to J.D. Salinger” New York Review of Books (48:10) 2001, 16-21

Lane, Gary: “Seymour’s Suicide Again: A New Reading of J.D. Salinger’s ‘A Perfect Day for Bananafish'” Studies in Short Fiction 10.1 (winter 1973) p 27-34 reprinted in Short Stories for Students Ed David A Galens Vol. 17. Detroit Gale, 2003 from Literature Resource Center

Moran, Daniel: “Critical Essay on ‘A Perfect Day for Bananafish'” Short Stories for Students. Ed. David A. Galens Vol. 17 Detroit Gale, 2003 from Literature Resource Center

Allsop, Kenneth: The Dissentient Mood “The Angry Decade: A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen-Fifties

Cotter, James Finn: “A Source for Seymour’s Suicide: Rilke’s Voices and Salinger’s Nine Stories” papers on Language and Literature 25.1 (Winter 1989) p83-98 reprinted in Short Stories for Students

In JSTOR

Levine, P: “JD Salinger: The Development of the Misfit Hero” Twentieth Century Literature 1958

Wiegand, W: “JD Salinger: seventy-eight bananas” Chicago Review, 1958

Baskett, SS: “The Splendid/Squalid World of JD Salinger” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, 1963

Smith, D: “Salinger’s Nine Stories: Fifty Years Later” The Antioch Review, 2003

Glazier, L: “The Glass Family Saga: Argument and Epiphany” College English, 1965

Boe, AF: For Seymour: With Love and Judgement” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, 1963

Bryan, JE: “Salinger’s Seymour’s Suicide” College English, 1962

Mazzaro, JL: “People in Glass Houses” The North American Review, 1964

Other sources

O’Hearn, S: “The development of Seymour Glass as a figure of hope in the fiction of JD Salinger” Open Dissertations and Theses, 1982

Themes and Discussion Points:

As you will learn if you browse the critical articles listed above, there are a myriad of things that Salinger scholars like to discuss when talking about “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.” Here is a list of critical questions that the articles above will help you answer.

1. Why do you think Seymour kills himself at the end of the story?

2. Why did the author choose that fate for Seymour?

3. How do you explain Salinger’s need to revisit the topic of Seymour so often in his later work? Do you think he regretted killing Seymour off in “A Perfect Day for Bananafish?”

4. What do you think of the way that shell shock/war trauma is characterized in the story? Do you think that Muriel is sympathetic to Seymour’s mental condition?

5. What is the significance of Sybil? Why do you think Seymour relates to Sybil better than to others?

6. What is the significance of feet in this story? Why does Seymour kiss the bottom of Sybil’s foot, and why does Seymour accuse the lady in the elevator of looking at his feet?

7. Why does Seymour want Sybil to look for Bananafish in the first place, and what is a Bananafish?

photo credit of Noah Sneider’s incredible work – http://www.noahsneider.com

Reader’s Guide – “Zooey”

Publication Details

The New Yorker, May 4, 1957 pages 32-42, 44, 47-48, 50, 52,54,57-59, 62, 64, 67-68, 70, 73-74, 76-78, 80-82, 87-90, 92-96, 99-102, 105-106, 108-112, 115-122, 125-139 (original appearance). Later published by Little Brown as Franny and Zooey in 1961, and dedicated to William Shawn.

Character List

Frances Glass (“Franny”)

A 20 year old college student

Zachary Martin Glass (“Zooey”)

Zooey is 25 years old. He is considered one of the most attractive and successful of the Glass children. It is noted that he is a successful television actor.

Bessie Glass

Irish-born family matriarch. Bessie worries about her children who have all seemed to grow up almost by themselves after years of success on “It’s a Wise Child.”

Les Glass

The absent father, Les is more or less only mentioned in “Zooey.” He is of Jewish descent and he and Bessie were successful Vaudevillians

Buddy Glass

Buddy is the second-oldest of the Glass children, he teaches at a women’s college.

Seymour Glass

Seymour has been dead 13 years during the course of events that composes “Zooey.” Franny says she wants to talk to Seymour and that doing so is the only thing that will make her feel better.

Plot Synopsis

“Zooey” continues the story of Franny’s “spiritual awakening” on Monday, two days after Franny’s trip to Princeton. The novella also gives the reader additional information about the unusual upbringing of the Glass children, whose radio appearances as child geniuses, has created a unique bond among them. Salinger indicates even more in “Zooey” than in other Glass family stories that the Glass siblings have a unique understanding of one another based on this shared experience.

The narrative opens with Zooey, smoking and soaking in a hot bathtub, reading a four-year old letter from his brother, Buddy. The letter encourages Zooey to continue pursuing his acting career. Zooey’s mother, Bessie, enters the bathroom, and the two have a long discussion, wherein Bessie expresses her worries about Franny, whose existential anxiety seen in “Franny” has progressed to a state of emotional collapse. During the conversation, Zooey vacillates between a sort of tit-for-tat banter with his mother and a downright rude dismissal of her and repeatedly asks that she leave. Bessie accepts Zooey’s behavior, and quips that he’s becoming more and more like his brother Buddy.

After Bessie leaves, Zooey gets dressed and moves into the living room, where he finds Franny on the sofa with her cat Bloomberg, and begins speaking with her. After upsetting Franny by questioning her motives for reciting the “Jesus Prayer,” Zooey goes into Seymour and Buddy’s former bedroom and reads the back of their door, which is covered in philosophical and literary quotations. After contemplation, Zooey telephones Franny, pretending to be their brother Buddy. Franny eventually acknowledges the ruse, but she and Zooey continue to talk. Knowing that Franny reveres their oldest brother, Seymour – the spiritual leader of the family, who committed suicide years earlier – Zooey shares with her some words of wisdom that Seymour once gave him. At the end of the call, as the fundamental “secret” of Seymour’s advice is revealed, Franny seems, in a moment reminiscent of a mystical satori, to find profound existential illumination in what Zooey has told her.

Between Grief and High Delight: The Glass Menageries of J.D. Salinger & Tennessee Williams

![]() Written by Angelica Bega Hart. December 2009. The author wishes to note that this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

Written by Angelica Bega Hart. December 2009. The author wishes to note that this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

Critics have often examined the underlying significance of religion in J.D. Salinger’s short fiction. This is entirely appropriate for a number of reasons, not the least of which is because what little we know about Salinger’s biography suggests that he avidly followed a number of religious traditions. As a young man growing up in a mixed religious household, as a Jewish soldier in World War II, and as more than a dilettante in the area of alternative spiritualities including Vedanta Hinduism, Zen Buddhism and even at one point, Dianetics, Salinger’s attention to religion seems tantamount to understanding his work. Moreover, there are both overt and covert references to Eastern and Western spiritualities in his fiction. The relevance of religious criticism has often predominated critical attention to Salinger’s 1957 novella Zooey.

Critical attention which has not centered on religion has often focused instead on elements of character or on the ephiphanic moment during the narrative’s climax. Seymour’s “Fat Lady” is one such primary target for debate. Furthermore, many psychoanalytic critics have investigated the relationship between Zooey and his mother Bessie. However, all of these critics may have missed an important corollary to Zooey, in Tennessee Williams’ popular 1944 drama, The Glass Menagerie. Apart from a mention in Gwynn and Blotner, [1] contending that Salinger fills a void left by post-war writers including Williams, and a brief, punning nudge to the play in Charles Poore’s New York Times Review of Franny and Zooey, [2] there is little mention of any connection between these two works of post WWII American fiction. While there are important differences as well, these works share more than a passing resemblance to one another. These similarities are most evident in the three main characters of each narrative. Other details of the stories mimic one another as well, as both employ elements of Romanticism and struggle with the idea of virtue. Both also deal with time and performativity in interesting ways in order to connect those elements thematically to the narratives. And ironically, both create some of the same mythic and symbolic connections.