MLA Citation:

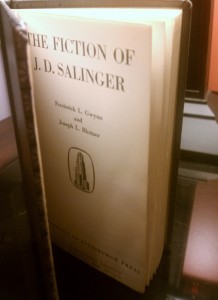

Frederick Gwynn and Joseph Blotner’s slender volume of commentary addresses the bulk of Salinger’s oeuvre. The body of the book is divided into three convenient sections and seven sections in total comprise the work.

First Paragraph:

“For the future historian, the most significant fact about American literary culture of the Post-War period may be that whereas young readers of the Inter-War period knew intimately the work of a goodly number of coeval writers (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, Wolfe, Sinclair Lewis, for example), the only Post-War fiction unanimously approved by contemporary literate American youth consists of about five hundred pages by Jerome David Salinger.”

Summary:

Introduction

The introductory section details the prevailing critical responses to Salinger’s work. They briefly describe the critical stance of critics Heiserman and Miler, David Stevenson, Ihab Hassan, Leslie Fiedler, Donald Barr, William Wiegand, and Maxwell Geismar, though they do not engage with their theoretical stances in the introduction.

Gwynn and Blotner also identify “For Esme-With Love and Squalor” the “high point of Salinger’s art” (for more information, see the “For Esme…” readers guide).

The Long Debut: The Apprentice Period (1940-1948)

This section discusses the twenty or so stories that appeared largely in magazines such as Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post, but also in a handful of others such as Cosmopolitan and Good Housekeeping). Gwynn and Blotner describe these as being of five types, “The Short Short Stories,” “The Lonely Girl Characterizations,” “The Destroyed Artist Melodramas,” “The Marriage in Wartime Group,” and “The Caulfield Stories.”