MLA Citation:

Goldstein, Bernice and Goldstein, Sanford. “Zen and Nine Stories.”. Renascence: Essays on Value in Literature: 22. (1970), pp. 171-82.

Publisher’s Abstract:

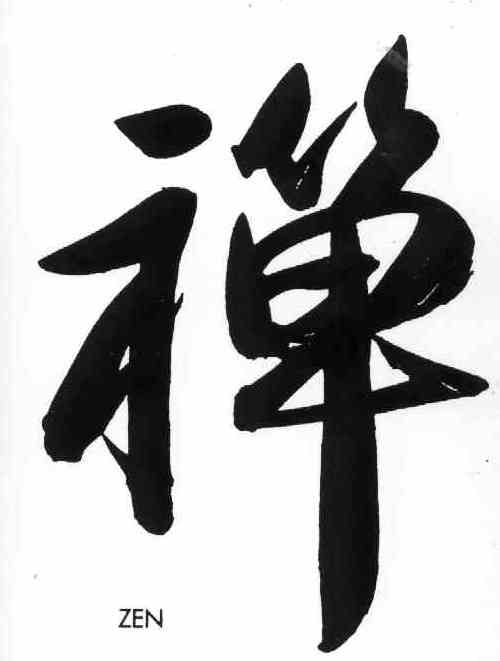

“Because Salinger has prefixed to Nine stories as a Zen koan, the Zen element in these stories ought to be investigated. The attempt to solve a koan (for example, the sound of one hand clapping) may lead, among several possibilities, to insanity or enlightenment. Thus one approach to Nine Stories is an examination of these two extremes of the koan experience. In such stories as “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut,” “The Laughing Man,” and “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” the destructive element is uppermost. In “For Esme – With Love and Squalor” and “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period,” the positive element of enlightenment. Since children come closest to the Zen experience (Teddy, for example), Salinger’s focus on children in these stories serves to sharpen differences between the enlightened and non-enlightened, the logical and illogical, the spontaneous and self-conscious. The rational adult world confronted by impossible choice (by koan) may react in a logically rational though destructive way, but the world of the child has perhaps not yet reached the stage where dichotomies prevent full immersion in each confronted moment.”