Readers Guide – “Hapworth 16, 1924”

Reader’s Guide kindly contributed by Kathy Gabriel. Thanks, Kathy!

Publication Details

Published in the The New Yorker, June 19, 1965, pages 32-113

Plot Summary

Buddy Glass, age 46 transcribes a letter written by his older brother Seymour at the age of seven, when both boys were attending summer camp at Camp Simon Hapworth. Seymour provides an emotional account of their time at Camp Hapworth interspersed with condescending advice to his family and rants on religion and literature in nearly 30,000 words. It was Salinger’s first and only published work after “Seymour: An Introduction.”

Continue reading “Readers Guide – “Hapworth 16, 1924””

Almost the Voice of Silence: The Later Novelettes of J. D. Salinger by Ihab Hassan

MLA Citation:

First Paragraph:

“Anyone who comments on the works of J. D. Salinger, nowadays, does so at his peril. There are many – editors, critics, friends, relatives, and plain readers among them – who are eager. to chastize the commentator for his indiscretion. This is just as well: one may thus feel free at last to say what one wishes. Where cannons and controversies reign, there is some freedom in playfulness.” (5)

Continue reading “Almost the Voice of Silence: The Later Novelettes of J. D. Salinger by Ihab Hassan”

Salinger Now: An Appraisal

MLA Citation:

Blotner, Joseph L. “Salinger Now: An Appraisal.” Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature 4.1 (Winter 1963): 100-08. Print.

First Paragraph:

“As I began to write this essay I had come to it fresh from reading three items that seemed to me suggestive in different ways. The first was a report that William Golding’s Lord of the Flies had overtaken and passed J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye as the most-read novel among young college readers. Also, I had just gone through a book entitled Salinger: A Critical and Personal Portrait, which contained nearly three hundred pages about the author contributed by twenty-five writers. Finally, I had seen a report that Salinger had given permission for the publication in book form of two more previously-published Glass stories, to be called Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction.2 These items suggested to me comments which I wanted to make about matters of change and stasis – to use a currently fashionable word – in the public and the criticism, and the work, respectively, of J. D. Salinger. In brief, it appears that he is now past the peak of the popularity he enjoyed in the late 1950’s. Further, Salinger criticism has now resolved itself into a dialogue in which the Anti’s, scarcely heard at first, now have substantial and vocal representation, a colloquy which has its own set of cliches and war-horse citations of evidence. The recent published and republished work itself is part of an extended phase of preoccupation with spiritual crises which has concerned the author for nearly ten years now, a phase in which the only change discernable has been an even more intense interest in the spiritual coupled with increasing experiment characterized most strikingly by prolixity of style. To indicate a further direction, all of this makes a Salinger adherent wish for certain things, almost for a moratorium now on Salinger criticism as well as for evidence that this gifted writer has assimilated the influences which have both informed and swamped his later work, evidence that he is ready to break through from a minor phase to a major one, as he once did earlier in his career.” (100)

Summary:

Written in 1963, Blotner’s article suggests the high point of Salinger’s popularity has passed, but leaves open the possibility (the hope?) that Salinger may still renew or even surpass his previous success. He writes:

…all of this makes a Salinger adherent wish for certain things, almost for a moratorium now on Salinger criticism as well as for evidence that this gifted writer has assimilated the influences which have both informed and swamped his later work, evidence that he is ready to break through from a minor phase to a major one, as he once did earlier in his career. (101)

He further notes that the “antis” (those who are more critical of Salinger’s work) have gained standing and that early critics who praised Salinger, while still in the majority have been increasingly silent. Therefore, Blotner is less optimistic about the state of Salinger criticism, stating:

one wonders how long, even with Catcher and the non-religious stories in the Salinger corpus considered too, such a relatively slim body of work can support such extensive analysis. (102)

Blotner begins the essay noting that William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies has overtaken The Catcher in the Rye as the most read novel among young college readers. He revisits this issue later in the essay as he discusses Salinger’s move away from dealing with the squalid world to dealing more exclusively with love.

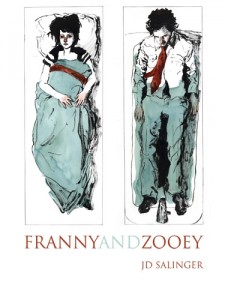

Reader’s Guide – “Zooey”

Publication Details

The New Yorker, May 4, 1957 pages 32-42, 44, 47-48, 50, 52,54,57-59, 62, 64, 67-68, 70, 73-74, 76-78, 80-82, 87-90, 92-96, 99-102, 105-106, 108-112, 115-122, 125-139 (original appearance). Later published by Little Brown as Franny and Zooey in 1961, and dedicated to William Shawn.

Character List

Frances Glass (“Franny”)

A 20 year old college student

Zachary Martin Glass (“Zooey”)

Zooey is 25 years old. He is considered one of the most attractive and successful of the Glass children. It is noted that he is a successful television actor.

Bessie Glass

Irish-born family matriarch. Bessie worries about her children who have all seemed to grow up almost by themselves after years of success on “It’s a Wise Child.”

Les Glass

The absent father, Les is more or less only mentioned in “Zooey.” He is of Jewish descent and he and Bessie were successful Vaudevillians

Buddy Glass

Buddy is the second-oldest of the Glass children, he teaches at a women’s college.

Seymour Glass

Seymour has been dead 13 years during the course of events that composes “Zooey.” Franny says she wants to talk to Seymour and that doing so is the only thing that will make her feel better.

Plot Synopsis

“Zooey” continues the story of Franny’s “spiritual awakening” on Monday, two days after Franny’s trip to Princeton. The novella also gives the reader additional information about the unusual upbringing of the Glass children, whose radio appearances as child geniuses, has created a unique bond among them. Salinger indicates even more in “Zooey” than in other Glass family stories that the Glass siblings have a unique understanding of one another based on this shared experience.

The narrative opens with Zooey, smoking and soaking in a hot bathtub, reading a four-year old letter from his brother, Buddy. The letter encourages Zooey to continue pursuing his acting career. Zooey’s mother, Bessie, enters the bathroom, and the two have a long discussion, wherein Bessie expresses her worries about Franny, whose existential anxiety seen in “Franny” has progressed to a state of emotional collapse. During the conversation, Zooey vacillates between a sort of tit-for-tat banter with his mother and a downright rude dismissal of her and repeatedly asks that she leave. Bessie accepts Zooey’s behavior, and quips that he’s becoming more and more like his brother Buddy.

After Bessie leaves, Zooey gets dressed and moves into the living room, where he finds Franny on the sofa with her cat Bloomberg, and begins speaking with her. After upsetting Franny by questioning her motives for reciting the “Jesus Prayer,” Zooey goes into Seymour and Buddy’s former bedroom and reads the back of their door, which is covered in philosophical and literary quotations. After contemplation, Zooey telephones Franny, pretending to be their brother Buddy. Franny eventually acknowledges the ruse, but she and Zooey continue to talk. Knowing that Franny reveres their oldest brother, Seymour – the spiritual leader of the family, who committed suicide years earlier – Zooey shares with her some words of wisdom that Seymour once gave him. At the end of the call, as the fundamental “secret” of Seymour’s advice is revealed, Franny seems, in a moment reminiscent of a mystical satori, to find profound existential illumination in what Zooey has told her.